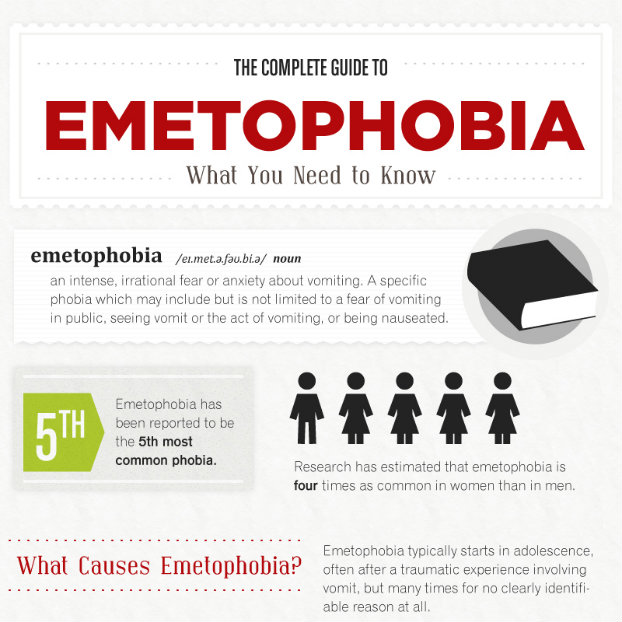

Scroll to the End of the Post to View the Infographic!

Dealing with the stomach flu-like symptoms — forceful vomiting, diarrhea, cramping — caused by norovirus is difficult enough for anyone, but when you add emetophobia to the mix, the experience can seem downright dreadful. In recent years, increased awareness and tracking of norovirus infections has made identifying it more common, making this nasty virus the leading cause of common gastroenteritis in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Every year in the U.S., about 21 million people – that’s approximately 1 in 15 – are infected with norovirus and develop an acute case of gastroenteritis; of these, about 70,000 cases end up in the hospital. Norovirus is also the leading cause of food-borne illness outbreaks in the country, says the CDC. Unfortunately, there’s no current vaccine for norovirus, and no drugs have been developed to treat it. Although most cases aren’t serious, about 800 deaths per year are attributed to these highly contagious viruses.

Understanding a little more about these nasty viruses and learning some steps you can take to help avoid coming in contact with them can go a long way in preventing norovirus from being something you need to live through.

What is Norovirus?

Norovirus is the catch-all name for a group of related viruses, all of which affect the stomach and intestines. Norovirus infection causes gastroenteritis, or inflammation of the intestines and stomach. Sometimes, norovirus is referred to as the “stomach flu,” although it is not actually related to the influenza virus. Norovirus may also be referred to as food poisoning, although food is not the only means by which it is transmitted.

Norovirus is the catch-all name for a group of related viruses, all of which affect the stomach and intestines. Norovirus infection causes gastroenteritis, or inflammation of the intestines and stomach. Sometimes, norovirus is referred to as the “stomach flu,” although it is not actually related to the influenza virus. Norovirus may also be referred to as food poisoning, although food is not the only means by which it is transmitted.

For emetophobics especially, norovirus can seem like your worst nightmare. Not only do symptoms include vomiting, but norovirus infection may also cause:

- Nausea

- Diarrhea

- Stomach cramps

- Low-grade fever

- Chills

- Headache and muscle aches

- Fatigue

When people are infected by norovirus, they generally experience abdominal pain, diarrhea and vomiting within 12 to 48 hours of exposure. Most of the time, symptoms only last from one to three days and go away without treatment but, according to the Mayo Clinic, infants, young children, the elderly, and people with pre-existing health conditions may be more likely to experience dehydration, a serious consequence of diarrhea and vomiting.

How it Norovirus Transmitted?

Norovirus is highly contagious, especially in crowded settings such as schools, nursing homes, hospitals, dormitories, prisons,  day care centers, and even cruise ships. The virus spreads quickly from person to person in four ways:

day care centers, and even cruise ships. The virus spreads quickly from person to person in four ways:

- Touching a contaminated surface or object then touching your mouth

- Being in close contact with an infected person

- Aerosolized vomit particles, or tiny bits of spray that contain viruses

- Consuming food or drink that’s been contaminated

Norovirus is spread by the fecal-oral route – which is just as disgusting as it sounds. The viruses are present in an infected person’s feces even when they don’t show any symptoms, so you can never be certain that someone isn’t infected just because they don’t appear to be sick. When someone comes in contact with fecal matter – usually due to using the restroom without washing their hands properly – then touches a surface, an object, a food product, or another person, the viruses spreads faster than juicy gossip.

In the U.S., about 80% of outbreaks take place between November and April, leading to norovirus’ nickname of “winter vomiting illness,” says the New York Times. However, norovirus infections can take place at any time of year.

In fact, more than half of the known food-borne illnesses in the U.S. each year are linked to norovirus, making it the leading cause of “food poisoning,” according to the CDC. Food contamination can take place at almost any point, from growing to shipping, preparing to serving. All it takes is contact with food handlers who are infected with norovirus – and food handlers are implicated in most food-borne cases.

Though it’s less common, foods can also be contaminated “at the source,” such as shellfish grown in water contaminated by sewage or produce that’s irrigated with water that contains fecal matter. Raw foods, such as leafy greens, fruits, berries, and molluscan shellfish (oysters) are the most common culprits, but any food can be affected through contact with a contaminated person, surface, or water.

How Can I Avoid Norovirus?

An important way to avoid norovirus is by practicing good hygiene. Wash your hands thoroughly and often, especially after using the restroom, changing diapers or touching something that is a common source of contamination. It’s also essential to wash hands before and after food preparation, serving and handling. Do not prepare food for others if you are sick.

An important way to avoid norovirus is by practicing good hygiene. Wash your hands thoroughly and often, especially after using the restroom, changing diapers or touching something that is a common source of contamination. It’s also essential to wash hands before and after food preparation, serving and handling. Do not prepare food for others if you are sick.

To get hands really clean and help prevent norovirus, the CDC recommends this hand-washing protocol:

- Wet your hands with clean, running water.

- Apply soap and rub hands together to form lather and scrub well.

- Scrub and rub hands for at least 20 seconds, getting lather on the back and front of hands, on the palms, between the fingers and underneath nails (it should take you about as long as it takes to sing or hum “Happy Birthday” twice).

- Rinse your hands well under clean, running water.

- Dry your hands using a clean towel. (preferably single-use as virus particles may end up on the towel)

- Use a towel to turn off the faucet.

Surprisingly, whether the water is hot or cold makes no difference, according to Dr. Ben Chapman from the USDA-NIFA Food Virology Collaborative (NoroCORE) Team at North Carolina State University. NoroCORE is led by Dr. Lee-Ann Jaykus, PhD and was awarded a grant by the US Department of Agriculture to partner with scientists and researchers from universities, hospitals, government agencies, and other institutions to study human norovirus in the hopes of designing effective prevention and control measures. Norovirus may survive in water temperatures that are far hotter than you would want to wash your hands in, so hand washing is really more about contaminated particle removal through scrubbing than killing viruses via heat from water temperature, explained Ms. Katie Gensel from NoroCORE. Dr. Chapman also recommends using paper towels to dry your hands when possible and skipping the air dryers because the friction of the towel drying is important in removing any particles missed during washing and because research has shown that warm air hand dryers can actually be a place where microorganisms accumulate – don’t blow those nasty germs all over your nice clean hands!

If running water and soap aren’t available, use an alcohol-based hand-sanitizer. Though alcohol-based hand sanitizers kill some germs, they’re not completely effective against norovirus, don’t work particularly well on soiled hands, and thus can’t replace hand washing. If hand sanitizer is all that’s available, use it properly to ensure it kills as many germs as possible. The Mayo Clinic recommends these steps for effective hand sanitizer use:

- Choose a hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol.

- Apply a generous amount to the palm of your hand; it should be enough to completely wet both hands and fingers, front and back.

- Rub your hands together, covering all surfaces of both hands, until your hands are completely dry.

Keeping Kids Healthy

Since children often come in contact with norovirus in settings such as schools or childcare settings, it’s essential teach them proper hygiene habits that can reduce their chances of contracting norovirus. You can help your child stay healthy by encouraging them to wash their hands often and teaching them proper hand washing technique. It may be hard to get children (and many adults) to wash their hands for the recommended 20 seconds, so have them sing or hum “Happy Birthday” or “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” twice while they scrub with soap.

Since children often come in contact with norovirus in settings such as schools or childcare settings, it’s essential teach them proper hygiene habits that can reduce their chances of contracting norovirus. You can help your child stay healthy by encouraging them to wash their hands often and teaching them proper hand washing technique. It may be hard to get children (and many adults) to wash their hands for the recommended 20 seconds, so have them sing or hum “Happy Birthday” or “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” twice while they scrub with soap.

Help them make a habit of washing their hands often during the day, especially after using the restroom, before eating, and before and after handling food. Put up charts at their eye level to remind them, or make a chart so they can get a sticker every time they wash. Keep a step stool in front of the sink and have brightly colored soap on hand to make the process easier and more fun.

If your child is in school or a childcare setting, speak with the teacher or provider about sanitation practices. Are children required to wash hands several times during the day, including – but not limited to – after using the restroom and before eating? Are diapering areas cleaned after each use? Are areas for eating well separated from areas used for diapering?

Safe Food Handling

Fruits, vegetables and shellfish are the foods most often associated with norovirus outbreaks. As a general category, the so-called “ready-to-eat” (RTE) foods- which have extensive human handling without a terminal heating step prior to consumption (think sandwiches, lunchmeat, salads)- are at the most elevated risk of norovirus contamination. Although cooking is the only way to inactivate norovirus specifically, you should always follow the general food safety practices discussed in this section. Keep in mind that these practices are designed to address bacteria, not viruses, and they may be less effective when applied for virus control! If you suspect food has been contaminated, don’t take a chance – throw it out.

Fruits and veggies need to be washed carefully in order to help rid them of micro-organisms. To get produce really clean, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln recommends washing them in running water, and letting the water go down the drain. Avoid soaking produce, as this may actually spread any bacteria or viruses from surface to surface. Instead, use a strainer or colander and rinse thoroughly under running water so microorganisms are allowed to disappear down the drain.

You should wash all produce, even fruits and vegetables with inedible rinds, such as oranges or melons. Use a vegetable brush or scrubber to scrub produce with thick skins, like potatoes or squash. Refrigerate produce immediately after cutting it; temperatures of 40 degrees or cooler reduce microorganism growth, while temperatures of 80 to 100 degrees encourage growth.

In recent years, a number of fruit and vegetable washes have hit the shelves. Most use a combination of chemicals to clean produce. North Carolina State University tested several of these washes, and found that distilled water, or water that’s been purified and filtered, was just as effective at getting produce clean of bacteria. The study also found that very clean tap water was effective at getting fruits and veggies clean of bacteria (but not necessarily viruses which as we’ve discussed, typically require cooking to be rendered safe).

Raw meat, chicken and finfish are rarely contaminated with norovirus, although they can be contaminated with bacterial pathogens. When cooking chicken, meat or fish, ensure that the internal temperature reaches safe levels to kill those microorganisms. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends the following safe temperatures, all measured in Fahrenheit:

- Ground meat – 160 degrees

- Chicken and turkey – 165 degrees

- Beef – 145 degrees

- Pork and uncooked ham – 145 degrees

- Pre-cooked ham – 140 degrees

- Fish – 145 degrees

- Leftovers and casseroles – 165 degrees

When it comes to foods like meat, poultry, and seafood, shellfish are the most likely to be contaminated with norovirus. Norovirus survives freezing, can withstand temperatures as high (or higher than) 140 degress Fahrenheit, and common cooking methods like steaming cannot be relied upon to inactivate noroviruses in shellfish. Raw shellfish consumption would certainly pose a risk.

Take precautions when handling and preparing foods and if you’re sick, leave the cooking to someone else for at least three days after you recover. Similarly, if you have a sick person in the house, they should avoid the kitchen.

Keeping it Clean

If a surface becomes contaminated with feces or vomit, immediately clean it with a bleach-based cleaner or other disinfectant. Clean up any “organic load” (fecal material, vomit, etc) before you use the bleach solution to disinfect the surface. To make your own norovirus-killing solution, combine 5 to 25 tablespoons of chlorine bleach per gallon of water. Leave the bleach solution on the surface for at least 5 minutes. Wipe with a clean, single-use towel and dispose of it properly. You may even want to consider repeating the decontamination procedure.

If a surface becomes contaminated with feces or vomit, immediately clean it with a bleach-based cleaner or other disinfectant. Clean up any “organic load” (fecal material, vomit, etc) before you use the bleach solution to disinfect the surface. To make your own norovirus-killing solution, combine 5 to 25 tablespoons of chlorine bleach per gallon of water. Leave the bleach solution on the surface for at least 5 minutes. Wipe with a clean, single-use towel and dispose of it properly. You may even want to consider repeating the decontamination procedure.

Pay particular attention to the bathroom, where fecal matter and vomitus are more likely to be present – and don’t use the bathroom to store food or dishes. (you’re not, are you?) When you’ve got a sick person in the house, clean the bathroom with a chlorine-based disinfectant often – and don’t miss the sink faucets or the door handles. A 2010 study by Harris Interactive found that between 20 and 33 percent of people using public restrooms didn’t wash their hands.

In addition, every time a toilet flushes with the lid up, it emits an aerosolized spray of its contents that coat bathroom surfaces. The Discovery Channel show MythBusters found that every single toothbrush left in a bathroom for one month tested positive for fecal matter, emphasizing the importance of effective cleaning practices, as well as keeping the toilet lid down when flushing.

Norovirus can survive on clothing and linens, as well as hard surfaces. Wash any soiled laundry items in a separate load. Try not to handle soiled items without protecting your hands with rubber gloves and avoid agitating the items while you’re handling them. Use detergent and hot water to wash, and choose the longest cycle possible. Dry on the highest heat setting and don’t take the items out until they’re completely dry.

Remember, the virus can persist for days – or even weeks – on surfaces, and cold, moist conditions help it survive even longer. On hard surfaces, such as faucets, counters and door handles, the viruses survive up to 12 hours; they can persist up to 12 days on soft surfaces, such as contaminated carpet, says Health Canada. Some studies say the viruses persist even longer.

Treating Norovirus

Most people who contract norovirus start to feel better within one or two days and don’t experience any long-term health effects. There’s no specific medication for norovirus, and antibiotics are ineffective against viruses.

For most patients, dehydration is the most significant problem. Dehydration symptoms include:

For most patients, dehydration is the most significant problem. Dehydration symptoms include:

- Decreased urination

- Dry throat, tongue and mouth

- Feelings of dizziness or vertigo when standing

- Sunken eyes

- Among children, crying without tears and unusual fatigue and fussiness

Prevent dehydration by drinking lots of fluids, avoiding those that contain alcohol, caffeine or lots of sugar. If your symptoms are particularly severe and / or you can’t stay hydrated, it’s important that you see a healthcare provider. Young children, the elderly and people with depressed immune systems or other serious health problems are at highest risk of becoming dehydrated from norovirus.

Coping for Emetophobics

For emetophobics, norovirus presents a host of issues, other than simply the gastro-intestinal discomfort. After all, this disease does cause vomiting, so if you contract it – or are responsible for caring for someone with norovirus – you’re almost bound to come into contact with vomit at some point.

In order to reduce the anxiety that norovirus can cause, focus on remaining calm through the use of relaxation techniques, such as diaphragmatic breathing and more advanced anxiety coping skills you can learn in the material we’ve developed for emetophobia. When your anxiety threatens to kick your breathing into high-gear, also known as hyperventilation territory, try this technique:

- Place one hand on your abdomen and the other on your chest

- Slowly breathe in for three counts until you feel the hand on your abdomen – but not the hand on your chest – rise

- Slowly exhale, flattening your abdominal muscles as you do so; the hand on your chest should not feel any movement

- Repeat for about five minutes

Practicing this exercise at least three times a day will provide you with a tool to help control the anxiety and panic you may feel when you, or someone else, vomits due to norovirus.

Though there’s not currently a vaccine for norovirus, work to create one is underway. The vaccine, which may be in the form of a nasal spray, could be available as early as 2016 (but may have to be administered more than once) – but until then, the best way to fight the norovirus is through good hygiene. That means washing hands often and thoroughly, keeping surfaces clean, taking precautions when handling food, and refraining from going to work or preparing food for at least three days when you feel sick.

Though norovirus’ effects are certainly unpleasant, they generally pass on their own quite quickly. With a focus on prevention – and the use of relaxation techniques – emetophobics can be confident they have nothing to fear!

(Click infographic image for full size view)

Help Us Increase Awareness and Prevent the Spread of Norovirus!

Here’s three things you can do RIGHT NOW to help people become more aware of norovirus and what they can do to help avoid it and stop spreading it to others:

1. Share this post on Facebook.

2. Post one of the Tweetables below on your Twitter stream.

3. Link to this page from on your own website or blog.

Leave a comment below and let us know what YOU did to help raise awareness or if you have any other questions to be answered in a future post!

Tweetables:

![]() The more information people know about norovirus, the less likely they are to catch and spread it and the better off we all are. Here are some great things to tweet, you’ll be able to review and edit your tweet before it gets posted to your stream:

The more information people know about norovirus, the less likely they are to catch and spread it and the better off we all are. Here are some great things to tweet, you’ll be able to review and edit your tweet before it gets posted to your stream:

- Over 21 million ppl yearly are infected with norovirus, see how many end up hospitalized: » tweet this «

- Learn the 4 ways norovirus is transmitted and how you can avoid catching it: » tweet this «

- 80% of norovirus outbreaks take place between these two months: » tweet this «

- How moms and dads can help protect their kids from catching norovirus: » tweet this «

This post was co-authored with Dr. Anna Kaplan, MD., an American Academy of Family Physicians board certified and licensed physician, writer, researcher, and mother from Thousand Oaks, California. It was reviewed and edited by Dr. Lee-Ann Jaykus, Dr. Ben Chapman, and Katie Gensel from the NoroCORE Team at North Carolina State University who generously volunteered their time and expertise.

This post was co-authored with Dr. Anna Kaplan, MD., an American Academy of Family Physicians board certified and licensed physician, writer, researcher, and mother from Thousand Oaks, California. It was reviewed and edited by Dr. Lee-Ann Jaykus, Dr. Ben Chapman, and Katie Gensel from the NoroCORE Team at North Carolina State University who generously volunteered their time and expertise.